All articles

Employers Rethink Drug Benefits As GLP-1 Coverage Forces More Active Cost Management

David E. Williams, CEO of Atumcell and President of Health Business Group, examines why soaring prescription drug costs, especially GLP-1s, have become a breaking point for employer healthcare budgets.

Key Points

Employers face rising prescription drug costs as high-priced therapies like GLP-1s move from niche use to widespread adoption, breaking long-standing assumptions about predictable benefit spending.

David E. Williams, CEO of Atumcell and President of Health Business Group, explains that misaligned incentives among drugmakers, PBMs, and policymakers keep prices high while shifting financial risk onto employer health plans.

Employers regain control by actively managing drug benefits through coverage conditions, cost-sharing tools, and tighter oversight rather than treating prescription spending as a fixed cost.

What’s changed is the combination of high-priced products and broad demand. It’s not just the price of the drug anymore; it’s the quantity.

For decades, employers treated prescription drug costs as a predictable line item: roughly 10% of the healthcare budget, an expense often balanced by savings from fewer hospitalizations. But the math no longer adds up. The pressure began when expensive specialty drugs for rare diseases hit the market. The model broke entirely when that high-price, low-volume formula was flipped for the masses, a change best seen in the explosion of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss. The result is forcing a difficult reassessment of healthcare benefits inside boardrooms across the country.

These insights come from David E. Williams, a veteran leader at the intersection of healthcare and business. As the current CEO of cybersecurity firm Atumcell and President of the consulting firm Health Business Group, Williams has spent over two decades advising private equity firms and their portfolio companies. His experience, which includes hosting the influential CareTalk podcast, gives him a clear view of the forces straining employer-sponsored healthcare.

"What’s changed is the combination of high-priced products and broad demand. It’s not just the price of the drug anymore. It’s the quantity," says Williams. For many employers, that pressure is creating a financial challenge, born from a system that started as a WWII-era workaround when wage controls made benefits a tool for attracting labor. The arrival of GLP-1s, prescribed directly to the employed population, creates financial pressure on employer plans that fundamentally alters their budgets. Projections show these drugs will increase premiums and add to the overall economic pressures they face amid reports of general drug price increases and surging insurance premiums.

A bad investment: "With GLP-1s, the employer’s costs are definitely higher in the first year. Then, if that employee leaves in three years, any long-term health benefit accrues to somebody else. The most likely scenario is that they stop taking the drug and gain the weight back, which negates the investment. This is the crux of what employers are facing," Williams says.

Too many cooks: Williams argues that high prices persist because too many players benefit from the status quo. Drug manufacturers are designed to maximize profit, not restrain prices, while pharmacy benefit managers sit in the middle with incentives that often cut against cost control. "They’d like you to think they make money by negotiating better deals, but it’s much more convoluted than that, and the result may be that prices don’t come down at all." Recent Federal Trade Commission findings and congressional scrutiny have underscored how little pressure the current system applies to reduce drug costs.

Chasing Headlines: Politicians, meanwhile, often chase headlines with narrow fixes targeting a "small number of drugs" for specific groups like the Medicare population, creating an illusion of progress. "There is a monopolistic element to drugs. Many have patent protection, and when you have a patented product, it has no direct competition. That is a circumstance where prices tend to go up, certainly not down," Williams states.

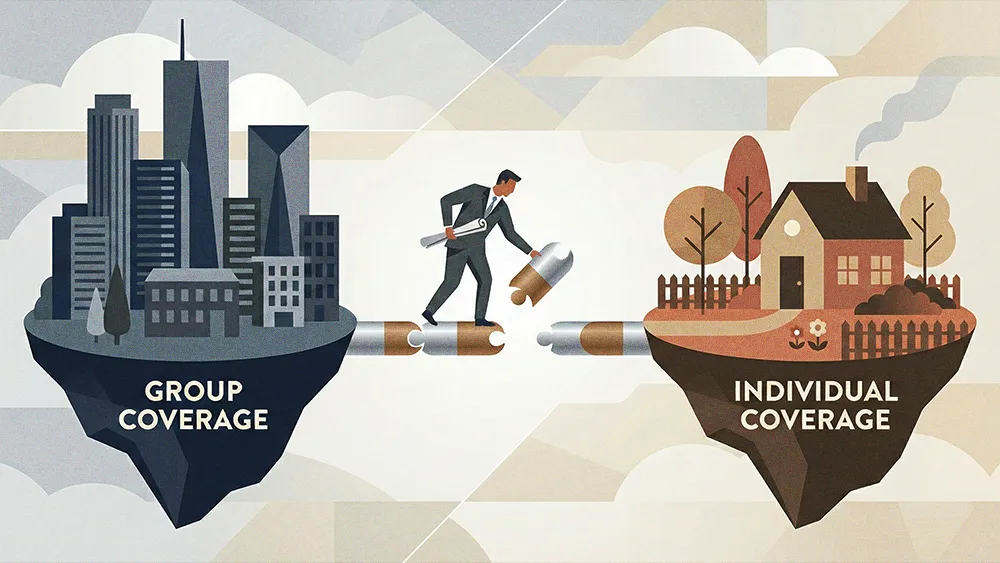

Unlike most other developed nations, the U.S. system has not historically included a single, central negotiator for drug prices. In other countries, the government acts as one powerful buyer, which economists call a monopsony, negotiating directly with manufacturers. The recent Inflation Reduction Act introduces a limited first move in that direction. While the change does not yet affect the commercial market, it signals a potential turn toward the negotiating power that has long been standard practice elsewhere. However, Williams notes that employers have several tools to manage these rising costs, rooted in established "managed care" principles.

Coverage with conditions: Rather than dropping coverage outright, some employers are adding guardrails to protect their investment. GLP-1 coverage is increasingly tied to mandatory enrollment in weight-management or nutrition programs aimed at improving long-term outcomes. "If employers are going to pay for these drugs, they want to make sure there’s surrounding support that gives them a chance to actually work," Williams says. Employers are also relying on established managed-care tools like prior authorization, which sets eligibility criteria such as BMI, and step therapy, which requires patients to try lower-cost generics before moving to more expensive branded biologics for chronic and autoimmune conditions.

Looking ahead, the challenge for employers is no longer whether prescription drug costs can be managed, but whether they are willing to manage them actively. As high-cost therapies continue to reach broader populations, benefit design, vendor oversight, and long-standing purchasing assumptions will all come under greater scrutiny.

Employers that treat drug spending as a strategic issue, rather than a fixed cost, will be better positioned to navigate what is becoming a permanent feature of the healthcare landscape, not a temporary disruption. Williams states "The belief that there's nothing employers can do about costs, that they can simply choose not to deal with them, is a misconception. There are things they can do," concludes Williams. "It may be difficult, but it can be done."

.png)