All articles

ICHRA Moves Health Insurance Risk Off Employer Balance Sheets and Into Defined Costs

Brad O’Neill, President and Managing Partner of The ICHRA Shop, breaks down how ICHRA is shifting health benefits from an HR function into a CFO-led financial strategy.

Key Points

Employers face unpredictable health insurance claims that create balance-sheet risk and make long-term cost planning difficult.

Brad O’Neill, President and Managing Partner of The ICHRA Shop, explains how ICHRA reframes benefits as a financial decision led by the C-suite.

ICHRA caps employer costs through defined contributions while shifting claims risk to the individual market, improving predictability when paired with smart policy design.

Employers didn’t start their businesses to run insurance companies. ICHRA gives them transparency and defined costs as adoption scales across the market.

What if health insurance no longer sat on the employer’s balance sheet as an open-ended risk? That question is pushing large companies toward Individual Coverage HRAs, where costs are defined upfront and claims volatility shifts out of the organization. For CFOs, ICHRA is emerging as a financial control lever that brings predictability to one of the most unstable line items in the business—healthcare spend.

Brad O’Neill has spent years watching employers rethink their relationship with health insurance. O’Neill is President and Managing Partner of The ICHRA Shop, and a founding member of the HRA Council. He's had a front-row seat to the evolution, giving him a unique perspective on how ICHRA represents a fundamental realignment of employer responsibility and financial exposure.

"Employers didn’t start their businesses to run insurance companies. ICHRA gives them transparency and defined costs as adoption scales across the market," says O'Neill. He believes ICHRA can change benefits from primarily an HR function into a financial strategy steered by C-suite executives. The defined-contribution model structure of ICHRA, for one, creates transparency for employers budgeting insurance costs. It also shifts plan selection from the employer to the individual market so employees can choose their own coverage, which increases carrier competition for enrollment. This shift in control, and the transfer of risk away from the employer, is what's driving large companies to ICHRA, even if it does require navigating the detailed rules of compliance.

C-suite, unite: ICHRA changes how benefits decisions get made inside organizations. O’Neill describes seeing CEOs and CFOs step in directly when the conversation turns to cost structure and risk transfer. In one case, he recalls leadership aligning quickly on an ICHRA move once it was framed as a financial decision rather than a plan design exercise. "It was the first time in twenty years I had seen a benefits choice made that way," he says.

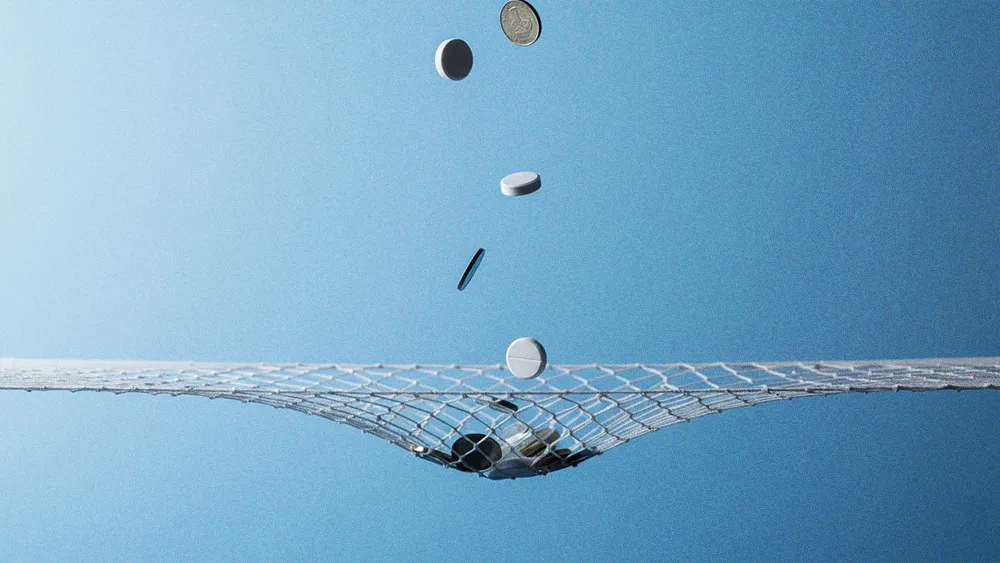

Let carriers carry risk: O'Neill illustrates the risk shift with a simple example. "Imagine an employer hires a healthy triathlete. A month later, a family member generates a million-dollar claim," he says. Under a self-insured plan, that exposure ultimately lands on the employer. With ICHRA, the employer’s cost is capped at a defined contribution, while claims risk is absorbed by the individual market carrier and spread across a broader pool.

There are some hurdles to wider participation, O'Neill explains, just not for the reasons you'd expect. Poor discovery, fragmented channels, and gatekeepers can limit adoption, while better onboarding, partnerships, and outreach would unlock broader participation and awareness.

Follow the bonus: O’Neill says broker compensation can influence how benefit options are positioned in the market. Traditional group and level-funded plans often come with established compensation structures, which can make newer models like ICHRA less familiar or less prioritized by some advisors. "Incentives matter in any market," he says. "Compensation structures naturally influence what gets discussed first." Over time, that dynamic may affect which employers explore which markets, creating what O’Neill calls a gradual shift in risk distribution.

The risk equation: O’Neill says the larger question is what happens as ICHRA scales across the market. Independent of intent, shifting more employees into the individual market changes the risk mix over time. He points to data from Wakely’s morbidity risk report as confirmation that the individual risk pool is trending sicker, not healthier, even after post-COVID utilization spikes were expected to normalize. "We thought claims would level out," O’Neill says. "They didn’t. And ICHRA becomes another variable that has to be managed at the system level—not avoided, but understood."

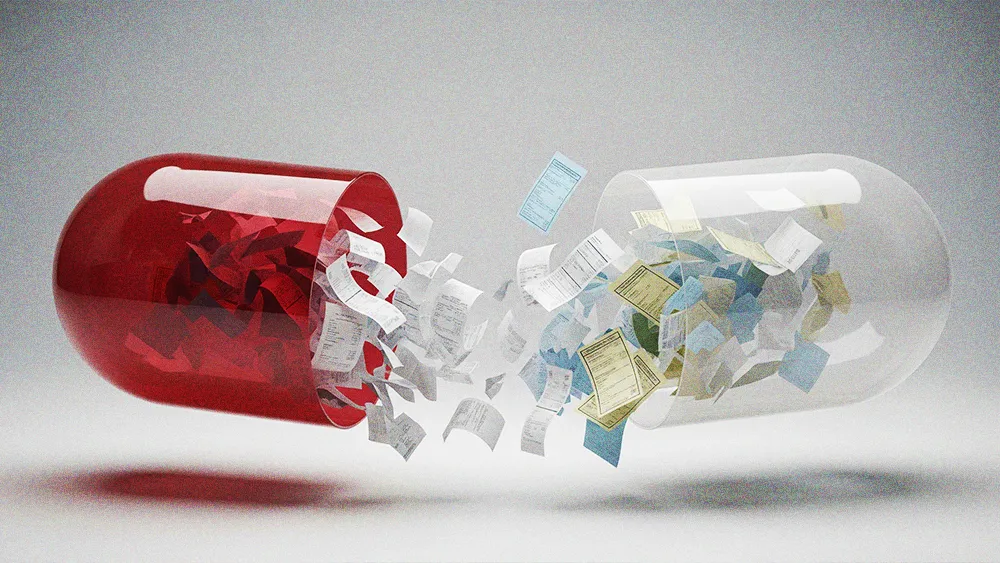

Creating the runway to ease ICHRA adoption requires a collaborative effort, O'Neill says. For one, he says the entire system needs to work together to maintain balance: "If you squeeze it on one side by pushing risk from self-insurance to the individual market, the balloon just bulges somewhere else. You still have the same amount of total risk." Efforts to codify ICHRA are building, and O'Neill points to his home state of Colorado as a prime example of how thoughtful policy design can create a stable environment. The state's use of a Section 1332 waiver for a federal reinsurance program is, as he puts it, "the perfect storm for ICHRA," an approach he credits with successfully stabilizing the individual market. "It lowered our rates and kept our risk pool stable." The lesson, he argues, is that ICHRA will always be most effective when paired with thoughtful policy design and market stability.

.png)